Versioning Containers and Iterators

The Problem

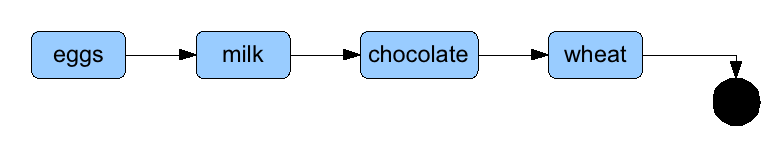

Okay, so let’s start this discussion with a simple linked list that contains the ingredients for Bill Cosby’s Chocolate Cake for Breakfast:

Normally we’d use a linked list in programming when we know we may have to arbitrarily insert items later on. For example, I just realized that this cake does not contain chocolate, so I should be able to insert that into the list by shuffling a little bit:

This seems like a much tastier recipe. But there can be a slight problem with this.

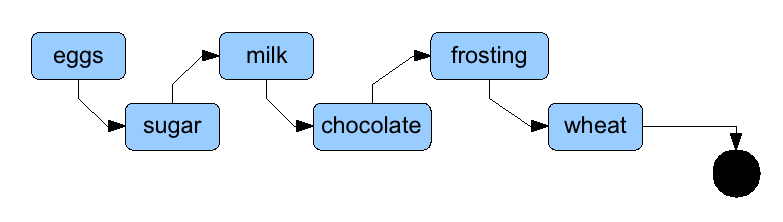

Suppose the linked list is serving as a model for your recipe view. You have a UI that accessess the model and then displays the results in some sort of view that you can see on your laptop in the kitchen. Suppose further that you decide to go even crazier and not just stop with adding chocolate, but you are also going to add sugar and frosting. INSANE!

This is not a problem yet. Likely your UI offers the ability to add new ingredients through the UI, so you just add them and the model gets updated, and when your view refreshes you see the new list:

That sounds like a great chocolate cake. But now suppose Mr. Cosby is on stage in Winnemucca doing his Chocolate Cake for Breakfast routine, and for some reason that nobody can understand the teleprompter that reminds him of the routine is using your data model to render the view – right at the exact moment in time that you are changing the recipe.

Uh-oh.

I’ve run into this problem a number of times in my software development career, where I have a data structure that is being accessed by more than one user at the same time. In our case, we have one read-only accessor and one read/write accessor. At first glance it doesn’t seem like this should be a problem. But unfortunately, even though the reader isn’t making changes to the model, the reader still depends on the model having a constant state.

There’s a couple of fairly simple ways to address this problem.

First, we can make a copy of the model for each user. We can have a resource that provides a copy when a user requests the copy. Then that user can do whatever they want with the model – read or write. When they are done, they can either discard their copy, or turn it back to the resource for the changes to be merged into the whole.

This might work for some implementations. In our trivial example here it would probably be just fine. But if I have a data structure with two million 50-byte records, this isn’t such a great idea. It isn’t just that I don’t want to make a copy of a 100 Mbyte (okay, 95 for you technicality folk) data structure – I don’t want to double my memory usage from 100 Mbytes to 200 Mbytes (or 95 to 190, sheesh). So making a copy won’t always work.

Another option is to lock the structure. Using some sort of a mutual exclusion primitive I can lock the data structure so that only one user can access it at a time. I can’t just hold the lock per-access, though – I have to maintain sessions and locks for the entire session. In other words, I have to make sure that nobody can change the recipe at all throughout the duration of Mr. Cosby’s act. This high level of granularity in the locking of the data structure makes it hard to use. And it is particularly frustrating for read-only users who are thinking, “Why can’t I access the structure? All I want to know is what is in it!”

Versioning

One way I’ve successfully solved this problem in production code is to use a versioned container and versioned iterators for that container. I used these at Volera, for example, for some reason that doesn’t matter now, because Volera is DEAD. Anyway, here’s how they work:

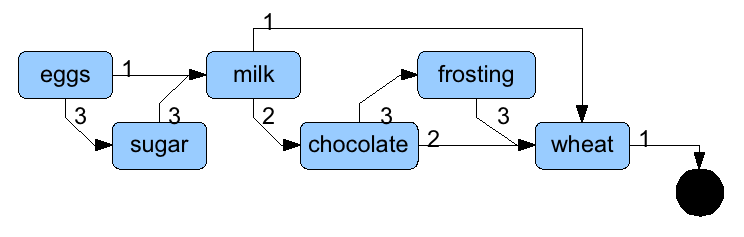

Versioned Containers act pretty much like regular containers – vectors, lists, hashtables, etc. The difference is that each link from one element in the container to the next has an associated version number on the link. Any given element can have a number of “next” links – even a singly linked list, like in our example. Each link would have a different version number. The container itself also has a version number, which corresponds to the highest numbered link in the container.

Versioned Iterators go along with the versioned container. When you request an iterator from a container, it gives the iterator a version number which corresponds to the current version number of the container at the time of request. The user requesting the iterator can also request a different version number.

Here’s what our data structure might look like if it were versioned:

This ends up working out pretty cool. Mr. Cosby can request a versioned iterator of the view when his show begins that displays the model as it is when his show starts. Let’s say that his iterator is version 1. That iterator traverses the list by only following links where the version number is less than or equal to the version number on the iterator. So it first goes to “eggs”, then follows link 1 to “milk”, then follows link 1 to “wheat”, then ends. It can be doing this at the same time that another user is changing the data structure, first by inserting “chocolate,” which creates the version 2 link from “milk” to “chocolate” and the version 2 link from “chocolate” to “wheat,” and later by inserting “sugar” and “frosting” as version 3. A version two iterator on the structure would start with “eggs” then follow the version 1 link (remember – less than or equal to the iterator version) to “milk.” But then it would follow the version 2 link instead of the version 1 link, so now it goes to “chocolate” instead of going directly to “wheat.”

The same goes for the version 3 iterator, which gives us everything in the data structure.

There’s a couple of issues you have to deal with when you implement a structure like this. First off, you need some sort of a scheme to go through the structure and prune it of old traversal versions. If I remember correctly, a scheme that will work to do this is to have the container itself remember how many users are accessing it and what versions they are at. When one iterator goes away, the iterator should report this back to the container. The container then looks to see if that iterator is the lowest-version-number iterator that it knew about. If it is, the container can go through and prune all of the links that are versioned at that number and below, as well as nodes in the structure that are only included in the structure by links at that version and below. So there’s a little bit of housekeeping that has to go on, but the container should be able to do this after iterators go away.

In other words, once Mr. Cosby’s show ends, the data structure that previously looked like Fig. 4 should end up looking more like Fig. 3.

Another problem to consider is this: If the data structure lives for a long time and has lots of accessors, it is possible for the version numbers to overflow. The overflowing isn’t necessarily a problem, though, as long as you keep track of what is really the oldest version in the data structure. Another way to do this is, as you prune the table, you can take the liberty of reversioning the table if there are no accessors to the table. Depending on your situation, you may never have a chance to lock the whole structure in order to reversion it, but the first option should be workable.

Lastly, since you have to version the links themselves, you might not be able to directly use standard containers; for example, if you are using C++ you might have to create your own linked list template with a list of versioned next pointers in each node, instead of implementing your versioned list container in terms of the STL list container. I never tried this so I’m not sure how it would work. When I did this, I did it using a tree container that was implemented in STL style, with versioning in the pointers and iterators. It was pretty cool.