Understanding Generative Thinking, Part 3 (or, How to prove your point with diagrams)

(If you have not read parts one and two, you probably should do that first.)

One of the great things about generative thinking is that it allows you to prove your point with diagrams. Notice here that I did not say, “demonstrate” your point. I said “prove” your point.

With generative thinking, if you like, you can draw a diagram that discusses your point. This is not that big of a deal. The big deal is, if anyone disagrees with your point, you can reference the diagram you just drew as proof that you are right!

Remember, part of generative thinking is that they have to accept whatever you say without questioning it. And don’t forget the advantages of shouting!

Here is a real world example of how this actually happened. I am not making this up. I have several witnesses that can vouch for the validity of this experience.

The topic of discussion was, communicating issues between individual contributors and management. The question was asked, “I don’t always feel comfortable communicating problems to my upper management. Sometimes I am asked to do something; I see a problem, but I am unsure how to communicate this problem to them effectively. Do you have any suggestions?”

It is very important that you do not forget this question, because it will NEVER BE ANSWERED.

Here is how the question was addressed.

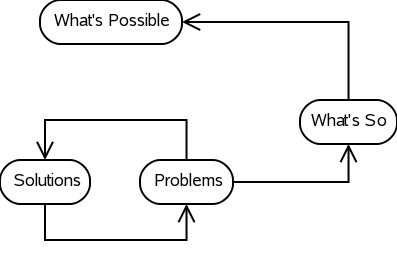

“Well, let’s take a look at this. What you don’t want to do is try to solve problems. I’ll show you.” And she drew this picture. “See, here you have your problems.”

“There’s something about problems. What do problems lead to?”

We answered, “Solutions.”

“That’s right. Solutions.” We were amazed we got this one right. She drew this next picture.

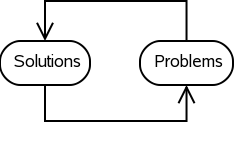

Then she went on. “See, the thing about problems is, in order to address the problems, we come up with solutions to the problems. But what happens when you come up with solutions? You simply find more problems!” And she drew this picture.

At this point, one person in the class took exception. “Uhh, well, I don’t agree. Sometimes, you identify a problem, and you solve it, and it just stays solved. Then you move on.”

Silly student! That is thinking about, not thinking for! The instructor of generative thinking is always right!

She returned to the board again. “No, I’m sorry, that is not correct. As you can see here on the board, problems lead to solutions, which lead back to problems. It is a vicious cycle. You don’t want to get caught up in trying to solve problems!”

Let me just say that not only will you not get very far telling software engineers, whose job it is to solve problems, that solving problems is a no-win game and a bad idea, but also it didn’t really fool anyone that she had just drawn a picture, and then used the picture to prove her point of view. Very interesting!

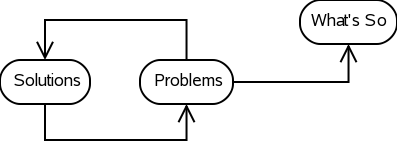

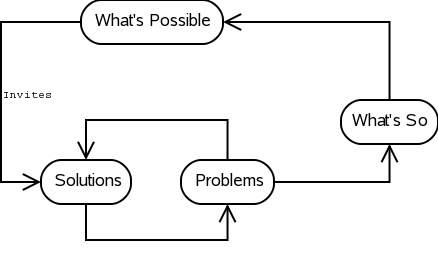

She went on. “Instead of trying to solve problems, you want to identify the ‘what’s so.’” She drew this picture. “You separate the fact from your opinion. That is what it means to identify the what’s so.”

(See, you can’t trademark the word “facts.” I wouldn’t be surprised if “what’s so” is a trademarked term.)

Next she drew this picture. “When you identify the what’s so, then you come up with what’s possible. This opens you up to discover creative ways of addressing the what’s so.” You see, no solutions to problems are ever creative!

Anyway, because you have identified the “what’s so” and have now had many edifying conversations about “what’s possible,” I’m sure you are wondering what happens next. So were we.

“Now that you know what’s so and what’s possible, the great thing about this is, it invites solutions.” And she drew this picture.

No, I’m not kidding.

We looked on in astonishment as we saw that we had just completed a larger circle. Most of us were truly trying to see this from her point of view and validate it. But we couldn’t help but notice that all we did is add two extra steps to the infinite loop we had originally!

As best I can tell, what this picture points out is the following: “Problems lead to solutions, which only lead back to more problems. This is how you address problems on your own. If you want to involve management, you must first identify the what’s so. Then you communicate it to management who tells you what’s possible. What’s possible might include things like, “If you don’t solve that problem, it is very possible that you will get fired.” Or, “If you don’t have enough time to solve that problem, it is very possible that you will need to work late nights.” Such possibilities obviously invite you to come up with a solution, any solution, to the problem.

And you’re right back where you started.

The moral of the story is, involving management in problem solving involves twice as many steps and takes twice as long. Otherwise, you can spin faster if you just deal with it yourself!

I related this story to my friend Brandon. After he wiped the tears from his eyes and got his breath back, he posited the following:

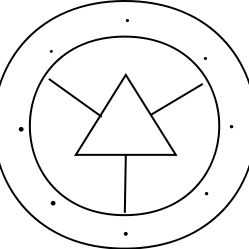

“The thing is, a problem is not an oval, it is a triangle. Each side of the triangle represents the three sides of the problem – my side, your side, and the truth. We draw a line out of each side of the triangle to represent the three sides of the problem. There is a circle that touches each of these lines. The circle represents you. Outside of you is a larger circle. This represents upper management. To solve a problem, then, you simply draw dots in the space between you and upper management. There. Problem solved.”

Here is the picture he drew:

We now call this the Hubcap Methodology of solving problems. And don’t go using it all over the place, willy-nilly. We are trademarking it.